An Education Disrupted

Thailand, 2014

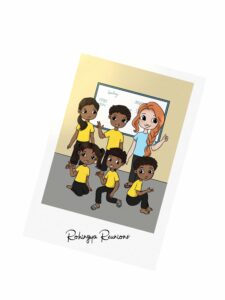

When I first set foot in the Grade 8 classroom in southern Thailand as an 18-year-old, I anticipated meeting a bunch of rambunctious 13-year-olds who were ready to walk all over me.

Instead, I came face-to-face with a group of students that were ages 16 – 18 years old.

The teacher was the exact same age as the students.

As if teaching isn’t hard enough, try building authority in a classroom among your peers as a first-time teacher. What a nice extra bonus.

But it wasn’t just Grade 8 that had older students. The ages ranged quite a lot among my students in Grades 5 – 8.

Why so many 18-year-olds in Grade 8?

To understand this, we have to dig a bit deeper into the Burmese migrant situation.

To do this, we have to look at the history of Burma – also known as Myanmar. It’s a bit of a messy history…and it doesn’t seem to be getting much better, post-COVID.

Myanmar is a culturally diverse country with at least 135 distinct ethnic groups. I instantly fell in love with the people of Myanmar and it quickly won the spot as one of my favorite countries in the world. A beautiful nation rich in resources and variety, it is sadly better known for its corrupt government and long-standing persecution of ethnic minorities.

After Myanmar gained independence from Britain in the late 1940s, it quickly fell into the hands of military dictatorship, so the people suffered from decades of repressive military rule.

The result? Widespread poverty, civil war with ethnic minority groups, suppression of freedom of speech, religious persecution, and genocide.

For decades, the people of Myanmar have fled their country to seek opportunity in neighboring countries. Some have fled for their lives, settling into refugee camps along countries bordering Myanmar.

Others have chosen to leave for economic reasons, seeking work in neighboring countries. They may not have fled for their lives, but their future in a new country is far from easy.

Burmese migrants find themselves working in low-paying, dangerous jobs. Sometimes they are not even paid at all.

From my limited high school education, I only associated the term, “modern day slavery” with the sex tourism, sweatshop, and diamond industries. I had no idea about the other industries that are notorious for trafficking and modern day slavery – fishing, construction, and agriculture.

Take fishing for example. If you’ve seen the popular Netflix documentary Seaspiracy, you might be familiar with the horrific labor conditions in the fishing industry. I’m only referencing this film because of the 10 minutes they touch upon the topic of slavery. This film went a bit hard on the “go vegan” messaging rather than uncovering more human rights exploitations, but it’s worth watching to get an idea of the fishing industry in Southeast Asia.

With an informal recruiting process for workers, widespread abuse and human trafficking becomes common in the fishing industry. Workers are often trafficked and tricked into work basically for free in the fishing industry. Trafficked workers are sold to fishing boat owners. There is a cost charged by traffickers and paid by fishing boat representatives for the fishermen. Because of this fee, fishermen are forced to work without pay until they pay off this “fee” – entering a dangerous indentured servitude. Some of them can go for months – sometimes even years – without pay. Working conditions are horrific. The fishermen work long hours with little food and water. For a deeper dive into the fishing industry, check out a report here that explains it a lot better than I can.

This is just a sample of what Burmese migrants face when seeking work in neighboring countries. Exploitation is nothing new. It’s been happening for decades now and there are a number of NGOs that are working to combat these injustices.

The Foundation for Education and Development helps Burmese migrants who are seeking opportunities in southern Thailand. With several programs to combat trafficking and empower migrant workers, one of them is the education center, where I worked.

As migrants, the students’ families traveled wherever they found seasonal work. Some months here, some months there. There weren’t always opportunities to go to school for them. With an education disrupted, they were in and out of school so often, it was hard to stay consistent in grade level. As a result, many of the children would find themselves working alongside their parents, joining the labor force at a young age to help put food on the table.

The school was built to provide a safe space for Burmese migrant children, give them access to education, and keep them out of the work force.

Keeping them out of work is easier said than done.

It’s common for Burmese children to work on the rubber plantations or in construction. These jobs generally had limited protective equipment, making the children vulnerable to job-related injuries. Underpaid and overworked, but often they had no choice – it was a way to support their family.

I taught English at the school. English was a helpful language for the children to learn as Thailand relies heavily on tourism. If they could speak English, they could find a higher-paying job outside of construction and agriculture.

I learned from my students about work on rubber plantations. There was one boy in the class who kept on falling asleep during my lessons. I saw it as rude, disrespectful, and a constant interruption in my classroom.

An insecure young teacher, I was put in awkward situation of confronting my student on his rude behavior. His answer was quite different from what I expected:

During the day, he went to school. At night, he worked on the rubber plantation. He explained to me the entire process of extracting rubber. His main job was the rubber tapping, the process by which latex is collected from a rubber tree. It is common for rubber tapping to take place at night due to the lower temperatures. This allows the latex to drip longer before coagulating. My visual descriptions are not quite up to par, so if a video helps, here you go.

He was the eldest son in his family, so it was expected of him to juggle work at night and school during the day. He was never a slacker in school. In fact, he was actually one of the top-performing students because of his ambition and hunger to learn. He knew that if he could learn English, he could get a higher-paying job in the tourist industry.

It was a common struggle to keep students in the classroom and out of work.

I always make the classic argument that education is a long-term investment and will open up doors of opportunity for the future.

But it’s hard to argue with a parent who needs food on the table tonight.

The only solution I had was to offer extra classes on Sundays outside of school for the students who dropped out. This ended up working out for those who couldn’t attend school during the week.

The constant fight of trying to keep the kids in school was a reality I never thought I would face. I come from a country where we dreaded waking up early to go to school. A high school diploma didn’t mean much to me. A bachelors degree doesn’t even hold much weight these days. A master’s or PhD, perhaps. Then you’re educated.

But there I was, face to face with peers of my age who were just grateful to make it past Grade 8, let alone receive a high school diploma.

It took moving across the world for me to realize just how much I took education for granted. And it took moving across the world for me to realize just how hard people fight for their education. Sadly, a lot of times, they lose the battle and end up in the workforce at age 12.

This just makes the fight for alternative, informal education all the more important (can I name drop Books Unbound here?).

If you want to take a deeper dive on the situation in Myanmar and where migrants & refugees go, check out reports by Fortify Rights.

I’ve been a fan of their work for years and always refer to their reporting. The dream is to one day work with them. Check them out!

Previous

The problem with the Five Year Plan

If you asked me about my Five Year Plan when...

Read MoreNext

American Burmese Celebrity

How to become a celebrity in a country that your...

Read MoreOther Posts | Rohingya

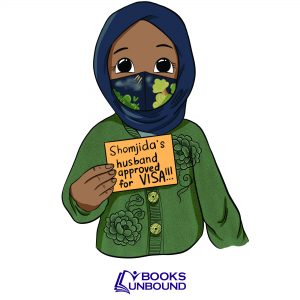

Rohingyalish Class

Who are the Rohingya? Where do they come from? These...

Read MoreAn Education Disrupted

It took moving across the world for me to realize...

Read MoreIntroduction

“What in the world am I doing here?” I stood...

Read MoreOne Day at a Time

Refugees do not assume they will be waiting for someone...

Read More